With tattooed arms left bare by a Vans muscle tank, a pair of tie-dyed shorts, and a head of green hair, Thatcher Bannon is impossible to miss. A few minutes into an interview at a coffee shop near Thunder Bay’s city hall, she’s already deep into a thorough rundown of the racial politics of her hometown.When a waitress responds to her request for the wifi password with a suspicious sounding “do you come here often?” Bannon stares at her.“I am here today,” the 22-year-old of Fort William First Nation replies, bluntly.“You have to have a tough exterior because you’re dealing with micro-aggressions everyday,” she said.“When those micro-aggressions are no longer micro-aggressions, and people are being outright racist and hateful, it starts to become a scary place,” she continued. “It can be terrifying, especially considering there has been deaths and the profiles fit Indigenous kids.”Bannon spoke to VICE News on a June afternoon, driving by the city’s waterways where the bodies of seven Indigenous teenagers have been found over the past 17 years.It all amounts to what many local Indigenous residents clearly say is a state of crisis. And with a new school year on the horizon, parents are pushing their leaders to come up with an alternative to sending their children into the city for classes.“They don’t want to send their kids to school, only to have them return in a casket,” Nishnawbe Aski Deputy Grand Chief Derek Fox told VICE News.VICE News spent several days in Thunder Bay speaking with First Nations youth on the ground about what it’s like to live in the city. In every interview, high school students, both current and former, recalled specific examples of being verbally and physically attacked because of their race. They talked about the difficulties they face being so far from home for the first time, how they navigate the big city, and what they want to see happen. High school is a trying time for any teenager. For First Nations students in Thunder Bay, it can feel more like a matter of survival. Many Indigenous students fly into the city from remote communities that dot northern Ontario because there isn’t a school that’s closer.Most of them land in a a place called Dennis Franklin Cromarty High School — DFC to those familiar with it. The school was established by parents and elders in the Sioux Lookout district and run by the Northern Nishnawbe Education Council, a First Nations nonprofit organization made up of more than 20 fly-in reserves.Signs of what school life is like during its condensed academic year were on full display on a recent visit — signage in both in English and Ojibwe, an elders’ room where students can spend their spare time doing traditional activities like beadwork and bannock, and the faces of smiling graduates plastered all over the walls.But outside the walls of the Indigenous high school, Thunder Bay is still a strange place for her.“I’ve had coffee thrown at me, and you often hear racial slurs,” Sakchekapo told VICE News. She doesn’t feel safe walking around Thunder Bay where she said racism is “normalized” and people “turn a blind eye.”Latoya Pemmican of Deer Lake First Nation said she often feels the stares of non-Indigenous people in the city. She’s been called a “savage” and a “dirty Indian.”Once, on the way to school, Pemmican overheard a conversation on the bus between two white people about an Indigenous person dying when one of them suddenly turned to her and said: “You’re Native and you shouldn’t be alive.”“Ever since I started talking about it instead of keeping it in, I realized that it happens to everyone all the time,” said Pemmican.

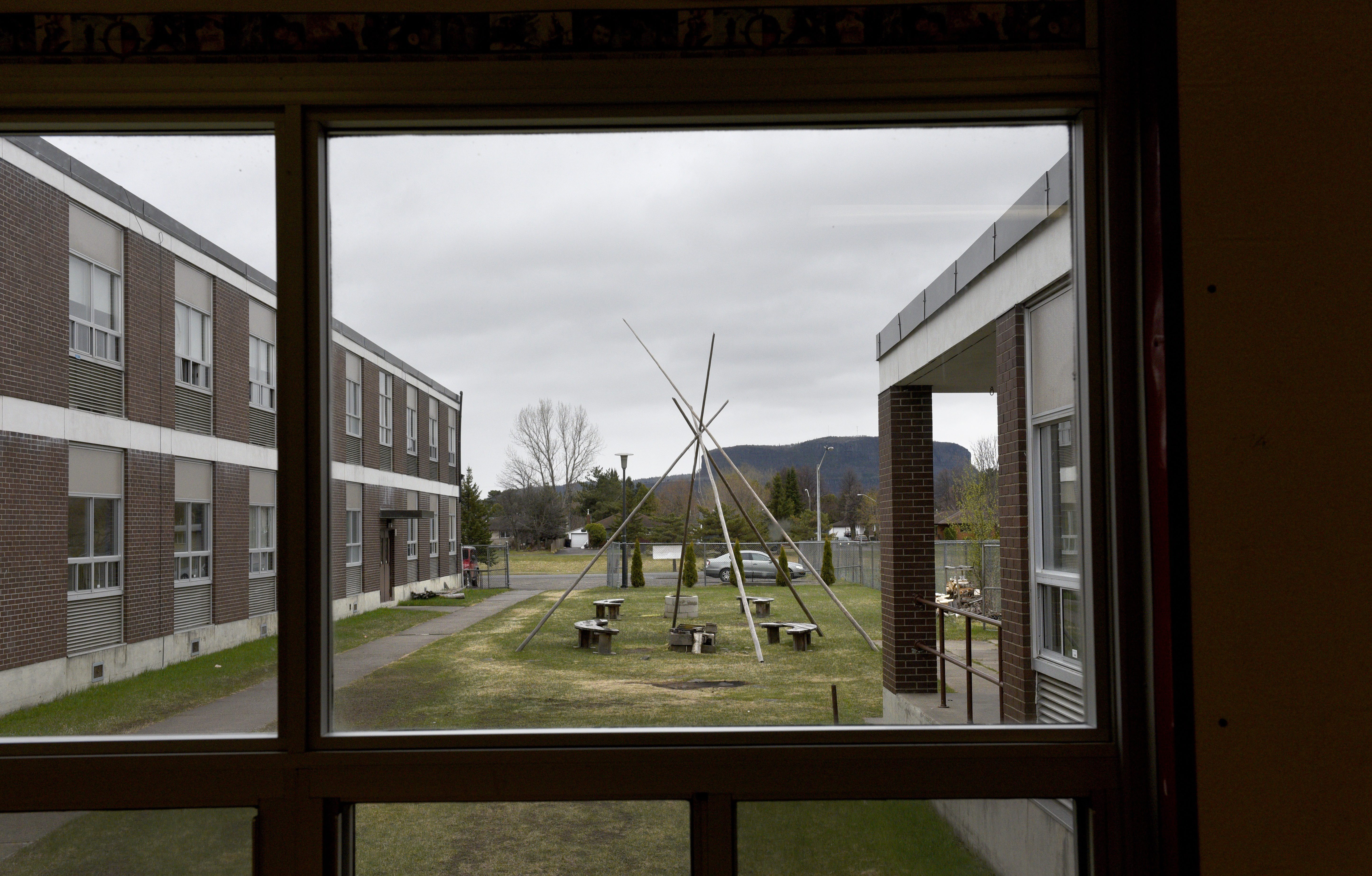

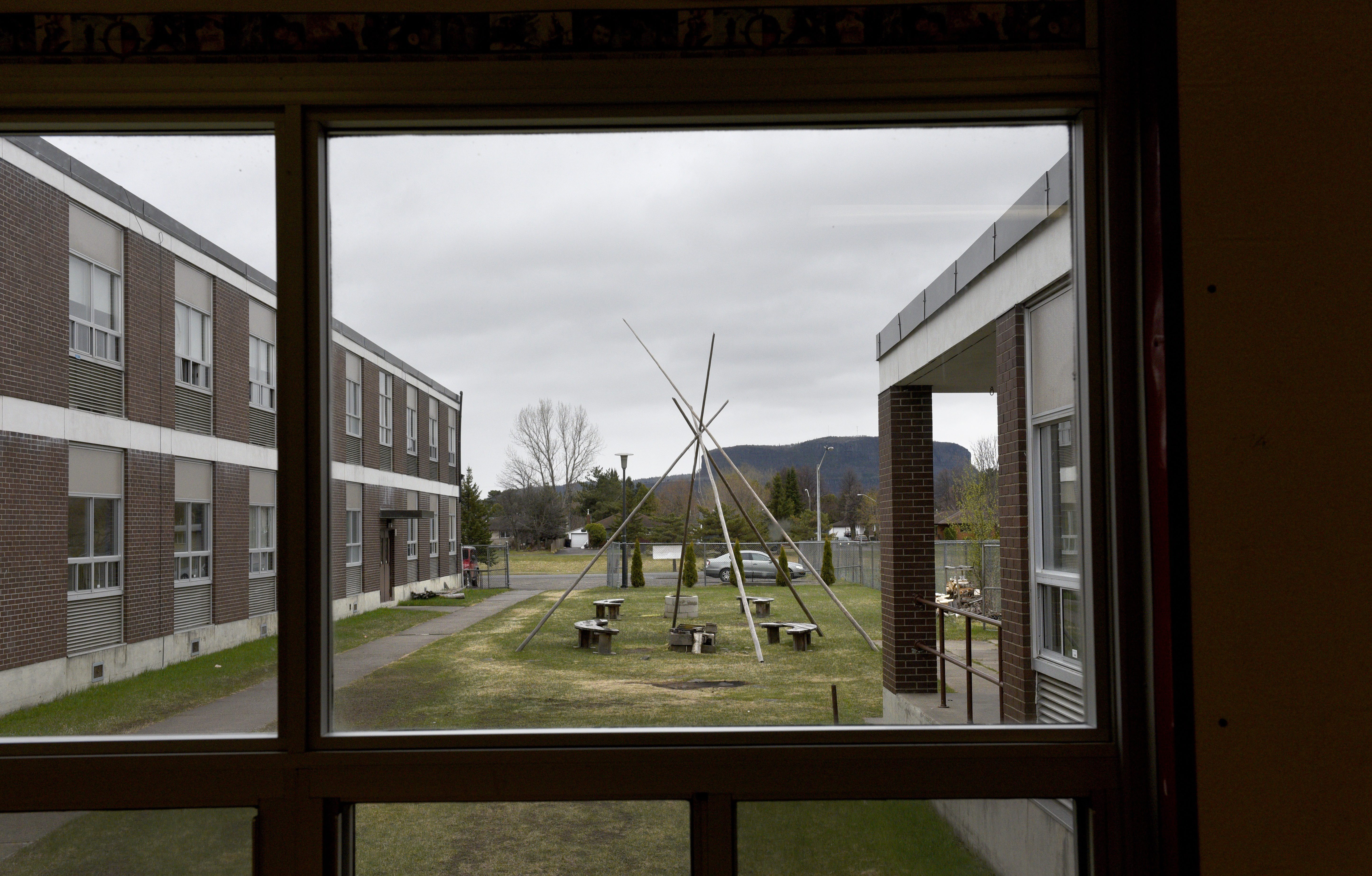

High school is a trying time for any teenager. For First Nations students in Thunder Bay, it can feel more like a matter of survival. Many Indigenous students fly into the city from remote communities that dot northern Ontario because there isn’t a school that’s closer.Most of them land in a a place called Dennis Franklin Cromarty High School — DFC to those familiar with it. The school was established by parents and elders in the Sioux Lookout district and run by the Northern Nishnawbe Education Council, a First Nations nonprofit organization made up of more than 20 fly-in reserves.Signs of what school life is like during its condensed academic year were on full display on a recent visit — signage in both in English and Ojibwe, an elders’ room where students can spend their spare time doing traditional activities like beadwork and bannock, and the faces of smiling graduates plastered all over the walls.But outside the walls of the Indigenous high school, Thunder Bay is still a strange place for her.“I’ve had coffee thrown at me, and you often hear racial slurs,” Sakchekapo told VICE News. She doesn’t feel safe walking around Thunder Bay where she said racism is “normalized” and people “turn a blind eye.”Latoya Pemmican of Deer Lake First Nation said she often feels the stares of non-Indigenous people in the city. She’s been called a “savage” and a “dirty Indian.”Once, on the way to school, Pemmican overheard a conversation on the bus between two white people about an Indigenous person dying when one of them suddenly turned to her and said: “You’re Native and you shouldn’t be alive.”“Ever since I started talking about it instead of keeping it in, I realized that it happens to everyone all the time,” said Pemmican. The difficulties are amplified for students who feel lonely, and don’t establish a connection with the people they are living with.“My first boarding house — she was kind of cold towards us,” said Sakchekapo of her boarding parent, who housed her, her older sister and her cousin. “She was very unfriendly, she didn’t try to interact with us, she didn’t try to bridge that gap.”The inquest jury into the student deaths made a slew of recommendations to improve the boarding situation, including figuring out best practices and standards for screening and vetting boarding parents, visits and inspections, criminal record checks, as well as training parents in things like CPR and managing intoxicated students.In its one-year progress report, Nishnawbe Aski Nation said the recommendation is “in progress” and a working group “will be established.” Meanwhile, some have taken matters into their own hands, with the Windigo First Nations Council, for example, starting up their own secondary programming, and taking over the handling of services that are currently run by Nishnawbe council.Earlier this month, First Nations chiefs, youth, and education leaders in the region came together in Thunder Bay to talk about student safety and the possibility of closing down the First Nations high school in the city at a meeting organized by Nishnawbe Aski.As a result of that two-day meeting, an emergency education task force will be formed to address the safety and wellness of students, do environmental scans of educational facilities and services, identify what other options exist for those who decide to stay in their communities, make sure resources are available for people who want to study in cities other than Thunder Bay, and create short term measures for those who do decide to come to Thunder Bay in the fall.The Thunder Bay Police Service didn’t show up to the meeting, which was open for anyone to attend, amid an investigation by the provincial watchdog that the police department is beset by “systemic racism.”The department has found itself at odds with Indigenous peoples in the city, given that it was quick to rule out foul play in the deaths of teenagers Tammy Keeash and Josiah Begg, whose bodies were found in the Neebing-McIntyre Floodway in May.Locals believe there is reason there to be suspicious. Many have begun to openly discuss the idea that there could be a serial killer targeting Indigenous youth — an idea for which there is little concrete evidence, but which has spun out of distrust and skepticism of the official investigation.Keeash was found with her face down among reeds in just a few inches of water, according to witnesses, with her pants at her ankles and her underwear pulled down. In Begg’s case, the police are still investigating and haven’t yet released a cause of death at the request of the family.Meanwhile, an inquest into the deaths of seven teens, five of whom were found in the city’s rivers found last year that the causes of four were undetermined.Acting Police Chief Sylvie Hauth wasn’t available for an interview. But spokesperson Chris Adams told VICE News in an email that “any racially motivated crime in this community is of great concern and is not acceptable.” The police iterated that they are waiting for recommendations from the independent police review body, and are working to cooperate with Indigenous leaders on how to move forward and repair relations. “We recognize the need for reconciliation,” Adams said.Mayor Keith Hobbs, who has since taken a leave of absence following criminal charges, has taken a harsher tone. The mayor, after several emails back and forth, did not respond to an interview request from VICE News, saying, “I’ve tried to put my voice in the story but my voice keeps hitting the cutting room floor. Why should I trust your media outlet to be any different?”In an earlier interview, Hobbs told Maclean’s that the notion of a serial killer targeting Indigenous kids was “ridiculous,” that a few racist incidents don’t define the city, and pointed to alcohol instead as the common thread.“If you are sitting, drinking at the top of a hill, chances are good that when you stand up, you’re going to fall down it,” he said, adding that the media were intent on making Thunder Bay look bad and blaming “high-priced Toronto lawyers” for the friction between Indigenous and non-Indigenous residents.He’s been hearing with increasing frequency that students don’t feel safe. The tips he offers to students often revolve around how they can better fit in and attract the least amount of attention to themselves as possible. He phrases it in terms of breaking down barriers, and bridging the gap.“If you dress like a gang [member] because you think it’s cool, the general public might associate you with that even though you’re not and you’re a student at DFC,” he tells the youth he works with. “If you are looking for an apartment and you’re putting on a t-shirt with a marijuana [sign] on it, the landlord is not going to be very willing to give you a chance.”

The difficulties are amplified for students who feel lonely, and don’t establish a connection with the people they are living with.“My first boarding house — she was kind of cold towards us,” said Sakchekapo of her boarding parent, who housed her, her older sister and her cousin. “She was very unfriendly, she didn’t try to interact with us, she didn’t try to bridge that gap.”The inquest jury into the student deaths made a slew of recommendations to improve the boarding situation, including figuring out best practices and standards for screening and vetting boarding parents, visits and inspections, criminal record checks, as well as training parents in things like CPR and managing intoxicated students.In its one-year progress report, Nishnawbe Aski Nation said the recommendation is “in progress” and a working group “will be established.” Meanwhile, some have taken matters into their own hands, with the Windigo First Nations Council, for example, starting up their own secondary programming, and taking over the handling of services that are currently run by Nishnawbe council.Earlier this month, First Nations chiefs, youth, and education leaders in the region came together in Thunder Bay to talk about student safety and the possibility of closing down the First Nations high school in the city at a meeting organized by Nishnawbe Aski.As a result of that two-day meeting, an emergency education task force will be formed to address the safety and wellness of students, do environmental scans of educational facilities and services, identify what other options exist for those who decide to stay in their communities, make sure resources are available for people who want to study in cities other than Thunder Bay, and create short term measures for those who do decide to come to Thunder Bay in the fall.The Thunder Bay Police Service didn’t show up to the meeting, which was open for anyone to attend, amid an investigation by the provincial watchdog that the police department is beset by “systemic racism.”The department has found itself at odds with Indigenous peoples in the city, given that it was quick to rule out foul play in the deaths of teenagers Tammy Keeash and Josiah Begg, whose bodies were found in the Neebing-McIntyre Floodway in May.Locals believe there is reason there to be suspicious. Many have begun to openly discuss the idea that there could be a serial killer targeting Indigenous youth — an idea for which there is little concrete evidence, but which has spun out of distrust and skepticism of the official investigation.Keeash was found with her face down among reeds in just a few inches of water, according to witnesses, with her pants at her ankles and her underwear pulled down. In Begg’s case, the police are still investigating and haven’t yet released a cause of death at the request of the family.Meanwhile, an inquest into the deaths of seven teens, five of whom were found in the city’s rivers found last year that the causes of four were undetermined.Acting Police Chief Sylvie Hauth wasn’t available for an interview. But spokesperson Chris Adams told VICE News in an email that “any racially motivated crime in this community is of great concern and is not acceptable.” The police iterated that they are waiting for recommendations from the independent police review body, and are working to cooperate with Indigenous leaders on how to move forward and repair relations. “We recognize the need for reconciliation,” Adams said.Mayor Keith Hobbs, who has since taken a leave of absence following criminal charges, has taken a harsher tone. The mayor, after several emails back and forth, did not respond to an interview request from VICE News, saying, “I’ve tried to put my voice in the story but my voice keeps hitting the cutting room floor. Why should I trust your media outlet to be any different?”In an earlier interview, Hobbs told Maclean’s that the notion of a serial killer targeting Indigenous kids was “ridiculous,” that a few racist incidents don’t define the city, and pointed to alcohol instead as the common thread.“If you are sitting, drinking at the top of a hill, chances are good that when you stand up, you’re going to fall down it,” he said, adding that the media were intent on making Thunder Bay look bad and blaming “high-priced Toronto lawyers” for the friction between Indigenous and non-Indigenous residents.He’s been hearing with increasing frequency that students don’t feel safe. The tips he offers to students often revolve around how they can better fit in and attract the least amount of attention to themselves as possible. He phrases it in terms of breaking down barriers, and bridging the gap.“If you dress like a gang [member] because you think it’s cool, the general public might associate you with that even though you’re not and you’re a student at DFC,” he tells the youth he works with. “If you are looking for an apartment and you’re putting on a t-shirt with a marijuana [sign] on it, the landlord is not going to be very willing to give you a chance.” Despite their challenges, both Sakchekapo and Pemmican agree shutting down the high school — which has become a second home for many of the students, and where many do feel safe — isn’t the answer. Instead, the grown-ups need to do more to engage with the students, many of whom are struggling with homesickness and culture shock.“I sat down and thought about it — all these things that are happening, it could happen to me, it could happen to my friends,” said Pemmican about the recent deaths of Begg and Keeash. “Maybe it is a good idea. But at the same time, I think of all the good things that come out of DFC, and and the pros are longer than the cons, even though cons can be very dramatic.”Bannon, who went to the provincially run St. Patrick High School, understands the appeal of DFC all too well — her own experience of high school was one of segregation and isolation, both in and out of the school. She remembers how at St. Patrick, Indigenous and non-Indigenous kids had their own turfs.On one side of the school was Moodie Street, where the white kids would gather, and on the other: “I can’t even tell you what that street was because we just called it ‘the Native side,’” she says, adding that the segregation felt systemic. The Indigenous kids’ lockers were all placed together, and the native language classes were held in the basement, right next to the pregnancy class, she says.And while she doesn’t consider the kind of advice Moffatt offers to be ideal, she agrees it’s the approach that needs to be taken.“If you want those kids to be safe, than you’re going to have to be giving them that kind of advice, and it’s very unfortunate,” she says.“It’s a generational ignorance. These are all old families that are here,” she says, looking down at the Kaministiquia River, where the bodies of two Indigenous teenagers — Jethro Anderson in 2000 and Jordan Wabasse in 2011 — have been been found.The giant Mount McKay looms on the other side of the river.For the Fort William First Nation, where Bannon is from, the location is sacred and spiritual. Sometimes, when she’s feeling down, she takes her Alaskan puppy to hike up the mountain.“It’s such a miserable place,” she says. “Sometimes when I get sick of Thunder Bay, I just go up there and forget everything.”

Despite their challenges, both Sakchekapo and Pemmican agree shutting down the high school — which has become a second home for many of the students, and where many do feel safe — isn’t the answer. Instead, the grown-ups need to do more to engage with the students, many of whom are struggling with homesickness and culture shock.“I sat down and thought about it — all these things that are happening, it could happen to me, it could happen to my friends,” said Pemmican about the recent deaths of Begg and Keeash. “Maybe it is a good idea. But at the same time, I think of all the good things that come out of DFC, and and the pros are longer than the cons, even though cons can be very dramatic.”Bannon, who went to the provincially run St. Patrick High School, understands the appeal of DFC all too well — her own experience of high school was one of segregation and isolation, both in and out of the school. She remembers how at St. Patrick, Indigenous and non-Indigenous kids had their own turfs.On one side of the school was Moodie Street, where the white kids would gather, and on the other: “I can’t even tell you what that street was because we just called it ‘the Native side,’” she says, adding that the segregation felt systemic. The Indigenous kids’ lockers were all placed together, and the native language classes were held in the basement, right next to the pregnancy class, she says.And while she doesn’t consider the kind of advice Moffatt offers to be ideal, she agrees it’s the approach that needs to be taken.“If you want those kids to be safe, than you’re going to have to be giving them that kind of advice, and it’s very unfortunate,” she says.“It’s a generational ignorance. These are all old families that are here,” she says, looking down at the Kaministiquia River, where the bodies of two Indigenous teenagers — Jethro Anderson in 2000 and Jordan Wabasse in 2011 — have been been found.The giant Mount McKay looms on the other side of the river.For the Fort William First Nation, where Bannon is from, the location is sacred and spiritual. Sometimes, when she’s feeling down, she takes her Alaskan puppy to hike up the mountain.“It’s such a miserable place,” she says. “Sometimes when I get sick of Thunder Bay, I just go up there and forget everything.”

Advertisement

It’s never been proven in court that any of those teenagers were murdered, but Indigenous residents are no longer accepting the official narrative that all the cases have been tragic accidents. For them, racism has never been an abstract concept but an inescapable reality of life off reserve — with potentially lethal consequences.This year, all those problems that often seemed tucked beneath the surface have come into glaring full view. In May, the bodies of two more youths, Tammy Keeash and Josiah Begg, were discovered in the city’s waterways within weeks of each other, with police quickly ruling out foul play.This month, Barbara Kentner, an Indigenous woman who was struck by a trailer hitch thrown out of a passing car, as someone yelled, ‘I got one’, died of her injuries, and charges have yet to be upgraded on the alleged assailant, a young white man. Add to that a litany of other hateful acts including alleged abductions and beatings, and racial tensions in the harbour town along Lake Superior are at an all-time high. The Ontario Civilian Police Commission has such “serious concerns” around policing in Thunder Bay, it announced this week that Senator Murray Sinclair, who led the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, would lead an investigation into the police services board. The police force was already under investigation for racism and how it deals with Indigenous deaths in particular. Meanwhile, the city’s mayor and police chief are facing unrelated charges around obstruction of justice.“I’ve had coffee thrown at me, and you often hear racial slurs”

Advertisement

Advertisement

DFC students, many of whom are the descendants of residential school survivors, are set up with boarding parents, and a “prime worker” that helps them navigate Ministry of Education-approved courses.For Alaina Sakchekapo of North Caribou Lake First Nation, DFC has been a sanctuary of sorts. She switched to the school after a semester at the provincially run Winston Churchill Collegiate and Vocational Institute.“There were so many students [at Winston Churchill,] and I wasn’t used to being around so many people at once, and it kind of made me very anxious,” she said. “I wasn’t used to everyone moving around so fast.”It’s a complaint echoed by many students who end up in high schools with a population almost three times the size of their reserves. North Caribou Lake, population 700, for example, is dwarfed by the hustle and bustle of city with 100,000 people. Just learning how to navigate the bus system on her way to school made Sakchekapo feel “small and insignificant.”Sakchekapo has thrown herself into studying and extracurricular activities, devoting most of her time to the school and its students, working her way up to the student services director position within the school’s student government.“We recognize the need for reconciliation”

Advertisement

Advertisement

“I sat down and thought about it — all these things that are happening, it could happen to me, it could happen to my friends”

Advertisement

Advertisement

Moffat Matuko, who runs an orientation program for First Nations students, works out of a former Chinese restaurant that’s been converted into an office for his youth multicultural centre. Next to it is Newfies Pub, which locals described as the worst bar in the city.As a black man who works with Indigenous people, Matuko isn’t naive to how immigrants and non-white people are perceived in Thunder Bay — he’s been called “Indian lover.”“It’s a generational ignorance. These are all old families that are here,”

Advertisement