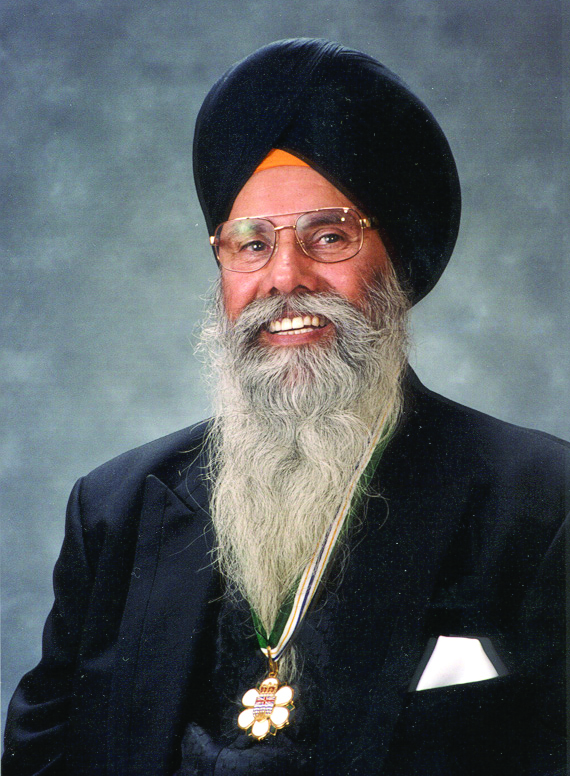

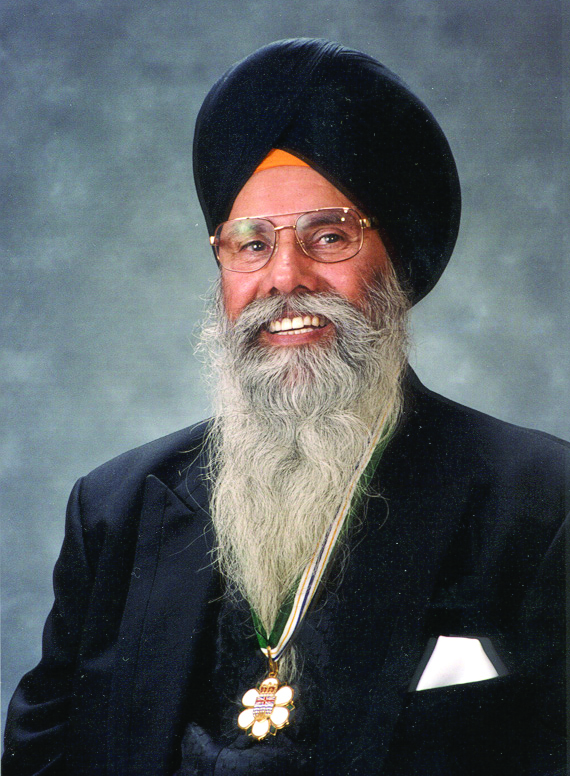

'It was the one decision in my life I regret the most': Gian Singh Sandhu on giving up his turban and beard in 1972. Photos submitted

Reading speculative headlines about a bombing in a Mississauga restaurant carelessly linked to Sikh extremism last month, I felt like I had stepped into a time machine. I remember a time when Sikhs with turbans were automatically assumed to be complicit in the Air India tragedy.“Hey, when are you guys going to blow up the next plane from the sky?” That was 1986, the words of a smiling young boy no more than 12 years old, waving at me from the sidelines during a stampede parade in my hometown of Williams Lake, BC. At the time, the comment caught me off guard and I felt gutted.When I first arrived in Williams Lake in 1970, the welcome my family received was nothing like the warm embrace that refugees from Syria and other conflict-torn nations find today. In the Canada of that era, visible minorities were looked at with trepidation. And talk about being visible! Wearing a turban meant you were routinely accosted with taunts like “Go home Paki.”As a community, we subscribed to the idea that if we worked hard and contributed to Canadian society, we would eventually be accepted as Canadians. Still, we often struggled with our identities as both Sikhs and Canadians. Often, we allowed ourselves to be convinced that the two were mutually exclusive. I was no exception. In the early 70s, after being told by my boss that my turban was holding me back from a promotion and a more successful career, I removed it. It was the one decision in my life I regret the most. It would be several years before I would strike up the courage to reclaim my Sikh identity. This kind of struggle was not unique to myself or even to Sikhs. It was the story of new immigrants of that era. What set the Sikh experience apart were a series of events that occurred in the 1980s that led to the demonization of the Sikh community.It began with the eruption of violence in Punjab, the traditional Sikh homeland. Punjab had once been an independent kingdom, before the British came in and usurped the different states of the Indian subcontinent and created the single entity called India. When they left in 1947, the country fractured along communal lines into Muslim majority Pakistan and Hindu majority India. The Sikhs of Punjab, a small minority then and now, opted to put their trust in and migrate to the Indian side. The cataclysmic event that broke that trust was the Indian government’s invasion of the Golden Temple, the most important place of Sikh worship, in June of 1984.The shockwaves of that invasion reverberated throughout the Sikh community. It led to the assassination of Indian Prime Minister Indira Gandhi in October of that year by her two Sikh bodyguards, and that assassination in turn fueled the massive state organized carnage that left thousands of Sikhs dead in Delhi and other cities in India.In Punjab, the invasion gave rise, overnight, to an independence movement that was barely a concept before, under the banner of Khalistan.In Canada, where there were by then some 200,000 Sikhs, there was hardly a family that was not personally affected—everyone still had close family in Punjab or other parts of India, and many had lost family members or knew of those that were tortured or killed in fake encounters.Canadian Sikhs responded by calling for the international community to put pressure on India to reign in its human rights abuses, to bring those responsible for the massacre of Sikhs to justice. The majority also sympathized with the call for independence that arose from Punjab. The World Sikh Organization of Canada (WSO), which became the largest representative Sikh body in Canada and of which I was a founding president, echoed these sentiments, calling for a peaceful resolution to the Punjab situation and a plebiscite on its independence. We believed then, as we do now, that the people of Punjab have a right to decide their own fate, and we supported nonviolent avenues to their self-determination if that is what Punjab decided.Outside of the mainstream of the Sikh community in Canada, a small few called for succession through violence. Unfortunately, it was those few who captured the media’s attention and those that the media chose to chronicle. The Indian government too capitalized on those individuals, at times even covertly supporting and provoking them, in a bid to create a narrative that equated any critique into its human rights abuses or any sympathy for Punjab’s independence with extremism. To the proponents of this narrative, the Air India tragedy in 1985 was like rocket fuel. Reasonable voices in the Sikh community, the voices of the vast majority of Sikhs, were drowned out and effectively silenced by the constant chorus of storylines around Sikh extremism.Over time, the ridiculous stereotypes of the fanatic Sikh gradually faded. As they did, many Sikhs also began to broaden their voice. The WSO, for its part, went from focusing on Sikh issues, such as the right to wear turbans in the RCMP and in Canadian Legions, to intervening on behalf of other religious groups before the Supreme Court, aligning itself with the Canadian Charter of Rights. When we threw our weight behind Bill C-38, the 2005 bill legalizing same-sex marriage in Canada, it was a watershed moment for the community.

This kind of struggle was not unique to myself or even to Sikhs. It was the story of new immigrants of that era. What set the Sikh experience apart were a series of events that occurred in the 1980s that led to the demonization of the Sikh community.It began with the eruption of violence in Punjab, the traditional Sikh homeland. Punjab had once been an independent kingdom, before the British came in and usurped the different states of the Indian subcontinent and created the single entity called India. When they left in 1947, the country fractured along communal lines into Muslim majority Pakistan and Hindu majority India. The Sikhs of Punjab, a small minority then and now, opted to put their trust in and migrate to the Indian side. The cataclysmic event that broke that trust was the Indian government’s invasion of the Golden Temple, the most important place of Sikh worship, in June of 1984.The shockwaves of that invasion reverberated throughout the Sikh community. It led to the assassination of Indian Prime Minister Indira Gandhi in October of that year by her two Sikh bodyguards, and that assassination in turn fueled the massive state organized carnage that left thousands of Sikhs dead in Delhi and other cities in India.In Punjab, the invasion gave rise, overnight, to an independence movement that was barely a concept before, under the banner of Khalistan.In Canada, where there were by then some 200,000 Sikhs, there was hardly a family that was not personally affected—everyone still had close family in Punjab or other parts of India, and many had lost family members or knew of those that were tortured or killed in fake encounters.Canadian Sikhs responded by calling for the international community to put pressure on India to reign in its human rights abuses, to bring those responsible for the massacre of Sikhs to justice. The majority also sympathized with the call for independence that arose from Punjab. The World Sikh Organization of Canada (WSO), which became the largest representative Sikh body in Canada and of which I was a founding president, echoed these sentiments, calling for a peaceful resolution to the Punjab situation and a plebiscite on its independence. We believed then, as we do now, that the people of Punjab have a right to decide their own fate, and we supported nonviolent avenues to their self-determination if that is what Punjab decided.Outside of the mainstream of the Sikh community in Canada, a small few called for succession through violence. Unfortunately, it was those few who captured the media’s attention and those that the media chose to chronicle. The Indian government too capitalized on those individuals, at times even covertly supporting and provoking them, in a bid to create a narrative that equated any critique into its human rights abuses or any sympathy for Punjab’s independence with extremism. To the proponents of this narrative, the Air India tragedy in 1985 was like rocket fuel. Reasonable voices in the Sikh community, the voices of the vast majority of Sikhs, were drowned out and effectively silenced by the constant chorus of storylines around Sikh extremism.Over time, the ridiculous stereotypes of the fanatic Sikh gradually faded. As they did, many Sikhs also began to broaden their voice. The WSO, for its part, went from focusing on Sikh issues, such as the right to wear turbans in the RCMP and in Canadian Legions, to intervening on behalf of other religious groups before the Supreme Court, aligning itself with the Canadian Charter of Rights. When we threw our weight behind Bill C-38, the 2005 bill legalizing same-sex marriage in Canada, it was a watershed moment for the community.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

Recently I was speaking to a group of young students at a Sikh school in Surrey, BC. I spoke about Vaisakhi, the yearly Sikh celebration that takes place on April 14. One of the children raised their hands and asked, “have you ever been called a terrorist?” I was stunned for a second and then, reflecting back on my 48 years in Canada, I said, yes, I have. I told them the story of that boy, in that parade long ago, and the constant stream of headlines that had created that stereotype in his mind.History repeats itself, they say, but in this case, that would be untrue. There has been no repeat of the circumstances of the 1980s that led to the demonization of the Sikhs then. In Canada, there has been no significant act of political violence connected to the Sikh community in over three decades. It is strange then to see the resurgence of those headlines, surfacing in a vacuum, without any material facts to support them.To the many young Sikhs alarmed by the recent media narrative, I have said and continue to say this: keep raising your voice amidst the cacophony, eventually your voices will be heard. Where the Sikh community once struggled with the stigma of extremism, its successes are also readily apparent today, in politics, in the arts, and in many other spheres of life in Canada. This is true for other communities as well, especially Muslims, who routinely face a similar barrage of reductionist narratives.To those in the media, I have this one piece of advice. Listen anew to the voices within the communities about whom you report rather than relying on old stereotypes and storylines. Communities evolve. You may be surprised by the richness of thought and expression that is waiting to emerge.Gian Singh Sandhu is the author of An Uncommon Road: How Canadian Sikhs Struggled Out of the Fringes and Into the Mainstream.