It was about 3 AM on the third floor of Aoyama Hachi, a perfectly dingy club in the Shibuya district of Tokyo with consistently on point house and techno music. After several hours dancing, my friends and I had worked up an appetite. As we headed downstairs, I spotted in the corner of the second floor, like a mirage in the room's disco ball fractals, a tong-wielding girl standing behind a table topped with a plate of flour-dusted buns, several toaster ovens, and a small sign reading "Nachopan".

Advertisement

In a city with a Murakami-esque, raining-fish-and-vanishing-cats countenance, you become used to its random acts of magical realism. And sure enough, the tong-wielding illusion with a charming little stall between the DJ-booth and shochu-lined bar was indeed preparing freshly made sandwiches and toasties for clubgoers.

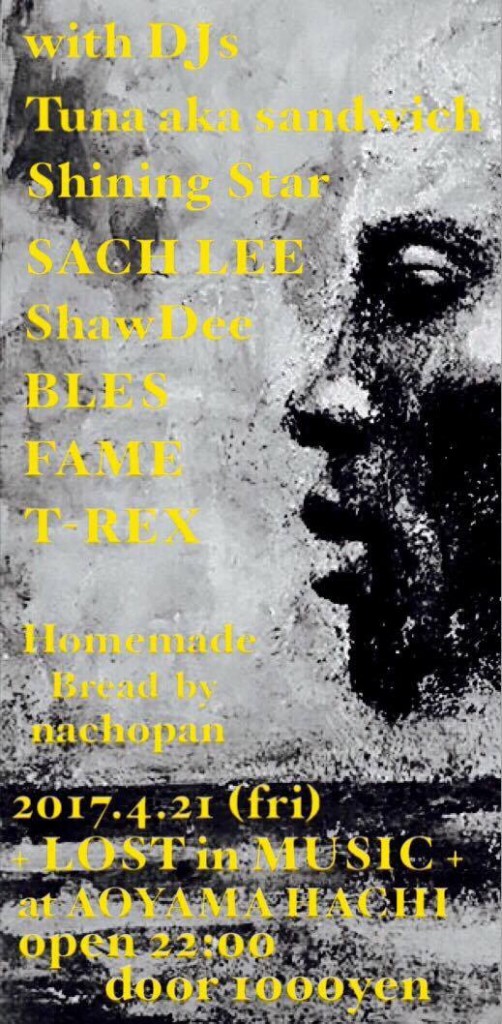

Nachopan is a one-woman pop-up bakery that's part of a small, but growing trend in Tokyo, where clubs have started taking their food seriously—to the point that flyers for parties list food purveyors alongside the names of headlining DJs. Food next to the dancefloor is usually limited to smaller or dingier venues rather than EDM superclubs or Roppongi meatmarkets. And Naho, the baker behind Nachopan, is at the forefront of the movement.

Several hours before my friend and I ordered Naho's gobo (burdock root) and yuzukosho (a pungent condiment made from yuzu zest) panini, as well as the white fish escabeche with lettuce and creamed potato, the self-taught artisan baker boarded the Tobu-Tojo Line across Tokyo with a suitcase full of all the trappings necessary for a mobile sandwich shop.READ MORE: These Wagyu-Filled Doughnuts Might Be the World's Most Indulgent Snack

What started as well-received gifts of her baked goods to friends on a night out a year ago, eventually turned into into Nachopan. Now, on any given weekend night, you can find Naho hidden next to one of Tokyo's dance floors. That means she has to lug an assortment of long-fermented breads, containers of hand-made fillings, a patterned tablecloth, wooden morizawa (serving platters), a cutting board, knives, a pastry brush, saibashi (long chopsticks used for preparation), tongs, and wax paper for wrapping food across the city.

Advertisement

Naho says she started her pop-up because she finds the impersonal nature of cafe work in Japan unfulfilling. As opposed to Western cafe and restaurant environments, employees in the hospitality industry in Japan rarely engage in casual conversations, which have a more formal customer-vendor relationship. And as customers place their orders with Naho at the club, it's never purely transactional. They ask her about the ingredients, cooking methods, and where else they can find her in the future, as they accumulate stamps in their Nachopan loyalty card. For Naho, this makes the long hours—she returns home around 8am—and physically demanding work worth it.READ MORE: A New Club Is Using Food Waste to Generate Energy

Naho reaches for her stack of tupperware treasure boxes, taking a spoonful of karanikumiso, minced meat mixed with spicy miso, and spreads it over her soft sandwich bread. She says her club-appropriate menu is based on " osake niau otsumami," foods that pairs well with alcohol. The admirable and ostensibly innate Japanese ability for such pairing goes well beyond the classic American greasy food to soak up the booze.

The mindset has origins in Edo-era sake no sakana, a traditional set of particularly salty, umami foods that complement sake. Originally these foods were things like shiokara (squid pickled in its own guts) and shuto (fermented bonito innards mixed with sake, honey, and mirin).

Advertisement

But such traditional foods would be a hard sell in a club, so Naho sticks with her Japanese-accented concoctions like kurosu-buta and yude-tamago sando, a sandwich of pork marinated in black vinegar, boiled egg, and lettuce; a toasted panini filled with karanikumiso and cheddar; and zunda muffins, small cakes flavored with a bright green sweet paste made from edamame beans, a specialty of Japan's Tohoku region, which pairs fantastically with Aoyama Hachi's shiso-infused shochu.

Bread, while not part of traditional Japanese cuisine, "has become part of daily life for many Japanese," Naho says, and "there is an abundance of varieties, many unique to Japan." Similar to other foreign-adopted cuisines in Japan (like French pastries, Italian pizza), Japanese bakers manage to come up with technically and creatively superlative versions: mugwort croissants, red bean pretzels, bread made from sake kasu (lees), and ;curry-filled donuts.

This kind of club music and food pairing is on the rise in Tokyo. At Aoyama Zero recently, a large pot of tonjiru (pork miso broth) brewed on a portable gas burner all night to be dished out alongside a plate of homemade salted onigiri sometime around dawn. A night of old soul and disco at Be-Wave's Soul Train night features handmade ekiben (train bento boxes). Gohan Disco ("food disco") is an event with different food-themed nights.Local DJ and promoter Hiro tells me that having food is a way make guests feel welcome. "It makes a comfortable zone," he says. "Tired people can take a rest and talk with friends. Also, when parties go very long people get hungry so it's nice if there is something to eat."