To most outsiders, Cuba is something of an enigma. During the more than half-century-long embargo that has restricted the free exchange of both goods and culture between Cuba and the United States, Americans have built a sort of impressionistic collage of what we think Cuba is like, and what sorts of things we think are common there: vintage cars, cigars, old guys in cool white hats. But what many of us stateside might not realize is that dairy, and ice cream in particular, is as integral to Cuban culture as Cohiba cigars.

In fact, Cuba is—and seemingly always has been—completely obsessed with dairy. The state of Cuban ice cream has, in fact, over the years, basically tracked the 20th-century political and social changes of the island nation. From the revolution to the modern shift toward a freer market, the story of Cuba’s ice cream is the story of Cuba itself—and it’s changing fast.

Videos by VICE

It all goes back to Fidel Castro, the communist revolutionary who seized control of the country in 1959 after a violent coup and retained control for longer than any other non-royal leader since Victorian times. Relations between the US and Cuba deteriorated shortly after Castro gained power. In 1962, then-president Kennedy famously bought 1,200 Cuban cigars just hours before expanding the trade embargo to consumer goods, including Cuban cigars. Less known is the fact that Castro, despite his frequent anti-United States diatribes, had his own shipment of forbidden Yankee pleasures. Once the embargo was in full effect, Castro had his ambassador to Canada send him 28 containers of ice cream from Howard Johnson’s, then the largest restaurant chain in the US.

Castro ate ridiculous quantities of frozen dairy. Colombian novelist Gabriel García Márquez, a close friend of Castro’s, recalled in a biographical essay that the Cuban leader once finished off a lunch with 18 scoops of ice cream.

As relations soured with the US, CIA plots kept in mind Castro’s famous appetite for ice cream. In 1963, the CIA worked with US-based mafiosi to ply a worker at the Havana Libre Hotel with a pill containing botulinum toxin and instructions to slip it into Castro’s daily milkshake. The plot was abandoned when the worker accidentally broke open the pill while trying to get it unstuck from the interior of the hotel’s kitchen freezer, where it had been stored.

Upon taking power, Castro made his dairy obsession state policy. Apparently, after trying each flavor of Howard Johnson’s ice cream, Castro declared that superseding the Yankee ice cream in quality would be one of the aims of his fledgling government. And as the years and decades went on, Castro quite publicly associated the maintenance of a healthy dairy industry with the success of his governance.

Countless historical anecdotes evince the passion with which Castro sought to bolster Cuban dairy. In 1964, he got in a fight with visiting French diplomat André Voisin, after Voisin refused to concede that a Cuban-produced Camembert was better than the French, though he admitted that it was “not bad.”

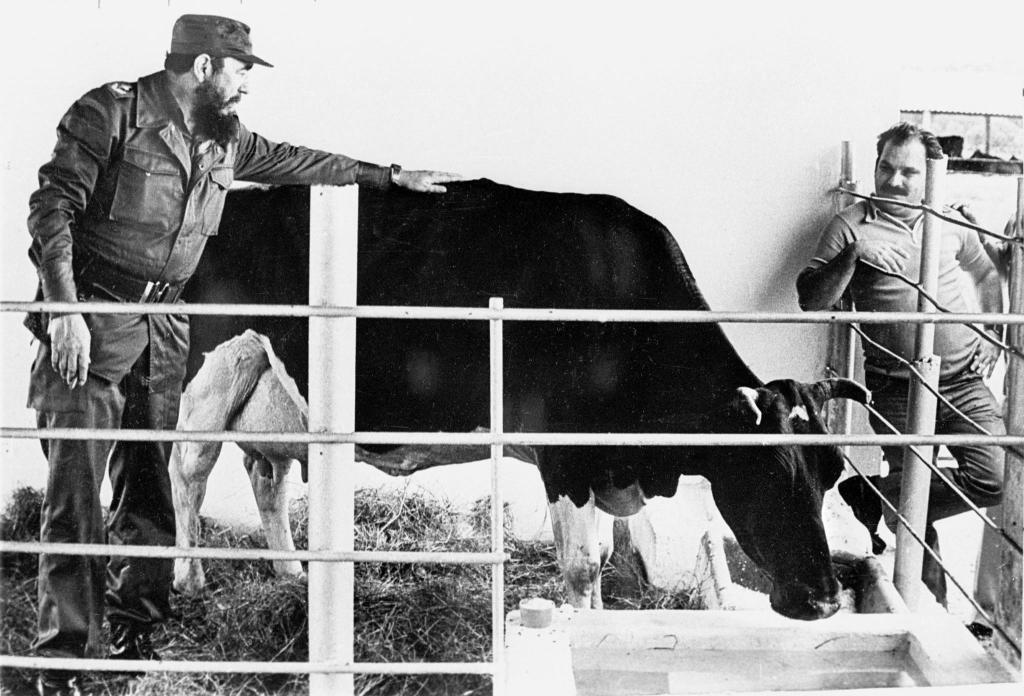

Castro assured that [Ubre Blanca] was provided special care, including a security detail and an air-conditioned stable where music was played during milking. He brought foreign dignitaries to visit the cow and spoke about her constantly.

Maintaining dairy production necessitated a healthy supply of milk, and prior to the revolution, most of Cuba’s cattle were Creoles and Zebus, neither of which is known for milk production. So Castro’s government purchased thousands of Holstein cows from Canada, and embarked upon a breeding program to hybridize a new breed of Holsteins that could survive the hot and humid Cuban climate. In 1972, Ubre Blanca was born.

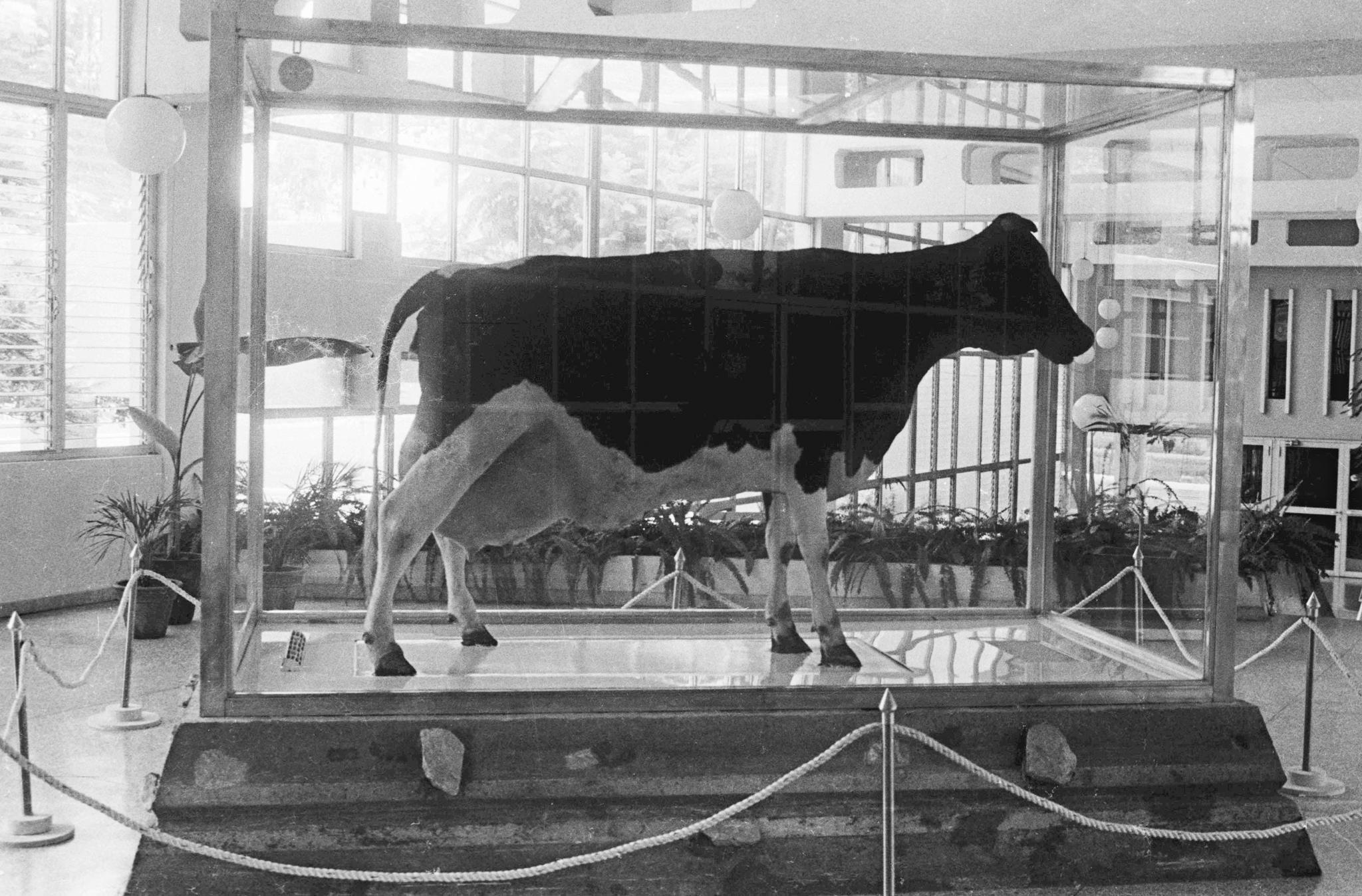

Ubre Blanca (“White Udder”), a hybrid Holstein cow, was perhaps Castro’s favorite Cuban citizen due to her prolific milk-producing abilities. In 1982, the Guinness Book of World Records certified her as the world’s highest-producing dairy cow, providing 110 liters in a single day. Castro assured that she was provided special care, including a security detail and an air-conditioned stable where music was played during milking. He brought foreign dignitaries to visit the cow and spoke about her constantly.

Ubre Blanca’s death was a national affair, garnering a full-page obituary in the state newspaper, as well as full military honors, a eulogy from the poet laureate, and a marble statue. As of 2002, Cuban scientists were working to clone the cow from genetic samples taken during her lifetime.

Though future Cuban Holstein hybrids failed to match Ubre Blanca’s prolific lactation, in 1987, Castro again tasked scientists with creating new cows to support domestic dairy production, this time focusing on a breed of mini-cows “the size of dogs.” A scientist who worked on the project told the Wall Street Journal that ideally families would keep their own mini-cows, which would feed on grass grown under fluorescent lights in each home’s drawers. The mini-cows never materialized.

In its general economy as well as more specifically in its dairy supply, communist Cuba was perpetually compelled to rely on imports and aid from its ideological and strategic allies. But when the proverbial specter of communism began to retreat from Europe, the island was left without subsidies. East Germany had been a major supplier of milk, and the Soviet Union of butter. In 1991, with East Germany merging with its Western counterpart and the Soviet Union on the brink of collapse, Cuba was forced to choose between milk and butter. Driven largely by the demand for ice cream, Cuban officials opted for milk.

Early in the communist reign, the crown jewel of Cuban ice cream quickly became, and remains, a Havana parlor called Coppelia. Castro put his personal secretary Cecilia Sánchez in charge of constructing an establishment to put the Yankees’ ice cream enterprises to shame, and she delivered.

Opening in 1966, Coppelia was designed by prominent modernist architect Mario Girona and was constructed to accommodate 1,000 people. It’s undeniably an architectural masterpiece, monopolizing a full block of prime real estate in Havana’s Vedado neighborhood.

Since its inception, Coppelia has been a testament to both the successes and the failures of the Cuban dairy industry, as well as a reflection of the island’s culture. In its heyday in the early 1980s, the place was serving 50 flavors to tens of thousands of customers per day, and satellite locations were operating elsewhere in the country.

But the collapse of the Soviet Union plunged Cuba into its most austere times, and for a while, Coppelia made ice cream with water instead of milk.

During those difficult post-Soviet times, Castro decided to use the American dollar as a second currency, reserved mostly for tourists and the wealthy. In 2004, the dollar was replaced by the convertible peso (CUC), which is worth many times more than the regular Cuban peso (CUP). Coppelia, always a visible demonstration of Cuban idiosyncrasies, has separate lines for those paying in CUC and those using CUPs; the CUC line, always significantly shorter, allows access to more flavors and apparently better-quality ice cream.

The rabid Cuban appetite for ice cream has always been on full display at Coppelia. People wait hours to order, and the most popular order is the ensalada, a sundae of five scoops. According to a Saveur report, most people order three of these, for a total of fifteen scoops each. Also a socio-cultural epicenter, Coppelia was the primary setting for what is perhaps Cuba’s most iconic modern film, the 1994 gay love story Fresa y Chocolate, in which a character’s sexuality is revealed by his order of strawberry rather than chocolate ice cream.

Long after the dissolution of the Soviet Union, Cuba eventually found solidarity with another modern communist nation: Venezuela; in 2012, Hugo Chávez announced that Coppelia would be coming to Venezuela.

In more recent times, the revolutionary spirit and government of Cuba has seemingly been in twilight. Castro relinquished power to his brother Raúl in 2006 and died in 2016; Miguel Días-Canel was sworn in as president as on April 19 of this year—the first non-Castro since the revolution. The Cuban economy in the 2010s has been stilted. Flavor options at Coppelia have dwindled to just a few, and a 2013 report from inside Cuba revealed that the parlor had been serving hollow scoops. An inability to buy high-quality feed has led to low-density and low-fat milk from domestic cows.

But in Castro’s later years and during his brother’s reign, Cuba has also seemed poised to pivot, although gradually, to a friendlier stance toward capitalism and foreign enterprise. Swiss confectionery giant Nestlé has been selling ice cream in Cuba for nearly 20 years, operating under a joint venture with a government-controlled corporation. Especially for younger Cubans, Nestlé’s name brand as well as its Linea Azul brand have gained recent popularity at the expense of establishments like Coppelia. This foreign company’s presence seems to be expanding in Cuba, with plans to open a new factory for the production of coffee, snacks, and cooking aids.

Even as Cuba tentatively opens its doors to capitalist enterprise, the nation remains enigmatic to foreigners, even to many of those who operate there. Curious about whether Nestlé uses imported or domestically produced milk in its Cuban-made products, I reached out to representatives from that company. Although the Switzerland-based representatives were eager to help me, they were (as of publication) unable to get responses from their Cuban partners, despite repeated attempts to contact them.

Despite Trump’s rebuffing of many of Obama’s diplomatic overtures toward Cuba, American investors are salivating over potential money-making opportunities on the island. The future of Cuba’s ice cream economy is uncertain. But whoever will make Cuba’s future ice cream, and however the economics are arranged, one thing is for certain: Cubans will eat tons of the stuff.

More

From VICE

-

Constantine Johnny/Getty Images -

(Photo by Elsa / Getty Images) -

Screenshot: Ubisoft -

(Photo by Ebet Roberts / Redferns; David Jon / Getty Images for HBO)